(chapter 15 in book)

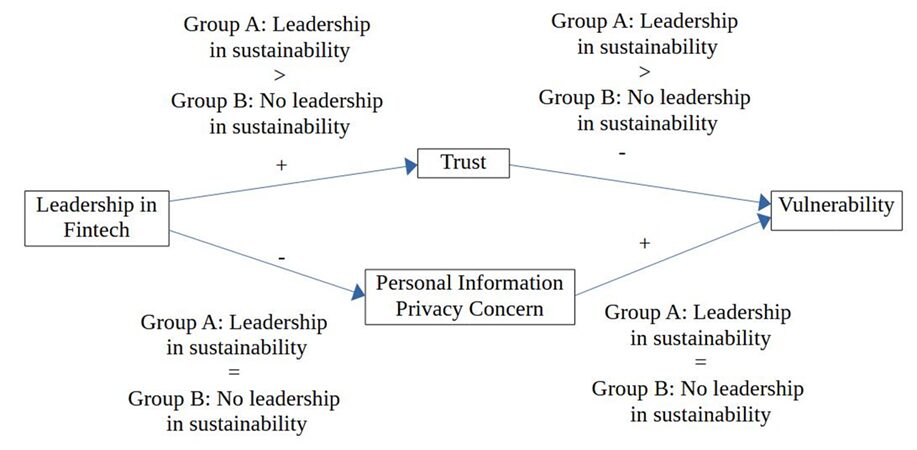

Fintech companies face the challenge of trying to lead in AI adoption while navigating potential pitfalls. The board of directors plays a critical role in demonstrating leadership and building trust with key stakeholders during the implementation of AI.

This research interviewed board members from Fintech companies to identify the most effective strategies for fostering trust among shareholders, staff, and customers. These three groups have different concerns and face different risks from AI. The findings reveal that the most effective methods for building trust differ among these three groups of stakeholders. Leaders should build trust for these three stakeholders in two ways: First, through the effective and trustworthy implementation of AI, and second, by transparently communicating how AI is used in a manner that addresses stakeholders concerns. The practical ways to build trust with the implementation and the communication for these three groups, shareholders, staff, and consumers, are presented in tables 1-3.

The findings show significant overlap between the effective overall implementation and governance of AI. However, several issues are identified that relate specifically to how AI innovations should be communicated to build trust. The findings also indicate that certain applications of Generative AI are more conducive to building trust in AI, even if they are more restrained and limited in scope, and some of Generative AI’s performance may be sacrificed as a result. Thus, there are trade-offs between unleashing Generative AI in all its capacity and a more constrained, transparent, and predictable application that builds trust in customers, staff, and shareholders. This balancing act, between a fast adoption of Generative AI and a more cautious, controlled approach is at the heart of the challenge the board faces.

Leaders and corporate boards must build trust by providing a suitable strategy and an effective implementation, while maintaining a healthy level of scepticism based on an understanding of AI’s limitations. This balance will lead to more stable and sustainable trust.

Table 1. How leaders can build trust in AI with shareholders

| Implementation 1) Use AI in a way that does not increase financial or other risks. 2) Build in-house expertise, don’t rely on one consultant or technology provider. 3) Make new committee focused on the governance of AI and data. Accurately evaluate new risks (compliance etc.). 4) Develop a framework of AI risk that board will use to evaluate and communicate risks from AI implementations. Management should regularly update the framework. 5) Renew board and bring in more technical knowledge and have sufficient competence in AI. Keep up with developments in technology. Ensure all board members understand how Generative AI and traditional AI work. 6) Make the right strategic decisions, and collaboration, for the necessary technology and data (e.g. through APIs etc.). Communication 1) Clear vision on AI use. Illustrate sound business judgement. Showcase the organization’s AI talent. 2) Clear boundaries on what AI does and does not do. Show willingness to enforce these. 3) Illustrate an ability to follow developments: Show similar cases of AI use from competitors, or companies in other areas. 4) If trust is concentrated on specific leaders that will have a smaller influence with the increased use of AI, the trust lost must be re-built. 5) Be transparent about AI risks so shareholders can also evaluate them as accurately as possible. |

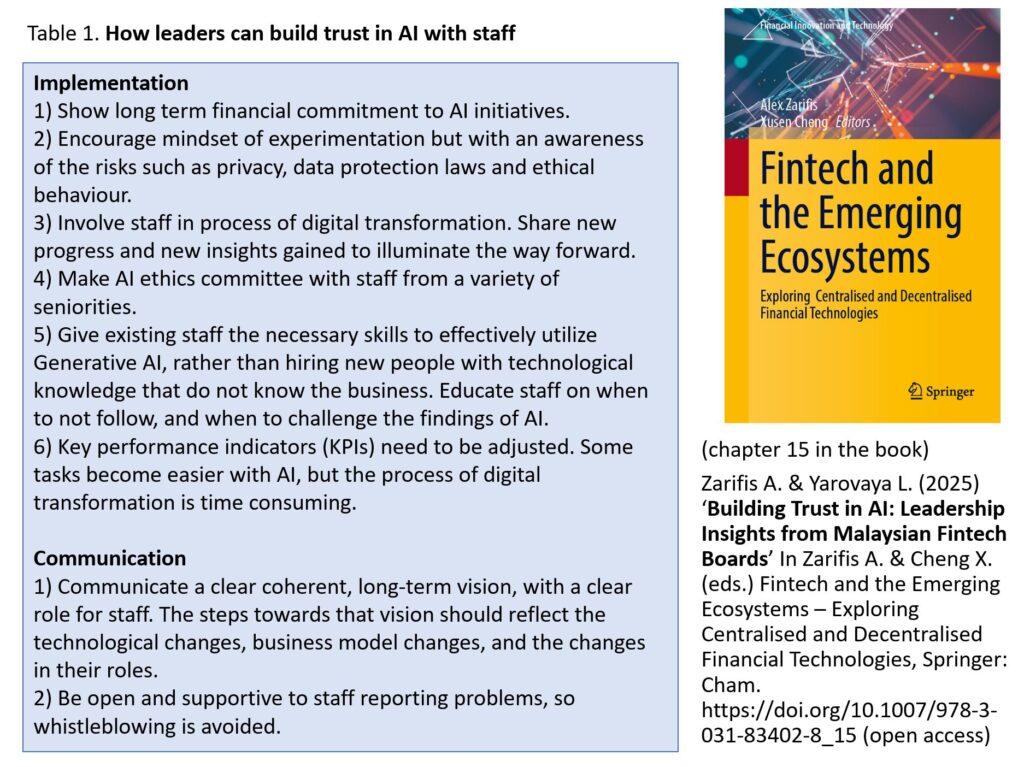

Table 2. How leaders can build trust in AI with staff

| Implementation 1) Show long term financial commitment to AI initiatives. 2) Encourage mindset of experimentation but with an awareness of the risks such as privacy, data protection laws and ethical behaviour. 3) Involve staff in process of digital transformation. Share new progress and new insights gained to illuminate the way forward. 4) Make AI ethics committee with staff from a variety of seniorities. 5) Give existing staff the necessary skills to effectively utilize Generative AI, rather than hiring new people with technological knowledge that do not know the business. Educate staff on when to not follow, and when to challenge the findings of AI. 6) Key performance indicators (KPIs) need to be adjusted. Some tasks become easier with AI, but the process of digital transformation is time consuming. Communication 1) Communicate a clear coherent, long-term vision, with a clear role for staff. The steps towards that vision should reflect the technological changes, business model changes, and the changes in their roles. 2) Be open and supportive to staff reporting problems, so whistleblowing is avoided. |

Table 3. How leaders can build trust in AI with customers

| Implementation 1) Avoid using unsupervised Generative AI to complete tasks on its own. 2) Only use AI with clear transparent processes, and predictable outcomes, to complete tasks on its own. 3) Have clear guidelines on how staff can utilize Generative AI, covering what manual checks they should make. 4) Monitor competition and don’t fall behind in how trust in AI is built. Communication 1) Explain where Generative AI and other AI are used and how. 2) Emphasise the values and ethics of the organization and how they still apply when Generative AI, or other AI, is used. |

The authors thank the Institute of Corporate Directors Malaysia for their support, and for featuring this research: https://pulse.icdm.com.my/article/how-leadership-in-financial-organisations-build-trust-in-ai-lessons-from-boards-of-directors-in-fintech-in-malaysia/

References

Zarifis A. & Yarovaya L. (2025) ‘Building Trust in AI: Leadership Insights from Malaysian Fintech Boards’ In Zarifis A. & Cheng X. (eds.) Fintech and the Emerging Ecosystems – Exploring Centralised and Decentralised Financial Technologies, Springer: Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-83402-8_15 (open access)